VODKA - THE VODKA GUIDE

ORIGIN

Perceived as an essential part of Slavic identity, vodka as we know it today was strongly influenced by the technological progress of the industrial revolution. Consumed in Eastern Europe since the 15th century, it was not until the 1930s that it entered the wider world as a ‘table spirit’, following widespread use of the column still.

EAST VS WEST

Initially produced for medical, military and industrial purposes, vodka spread in Russia from 1895 onwards, much helped by nationalisation, wiping out all traces of the rye-based spirit that until then had been made in pot stills. Vodka and its flavoured versions began to conquer Western Europe and the United States in the 1950s, eventually becoming a mainstay of the ‘back bar’. Exploring and experimenting with different ways of making vodka themselves, the United States and France in particular, began to compete with these traditional vodkas, meeting with the disapproval of the Slavic countries, who required a spirit with more aromatic complexity.

THE SPREAD OF THE WORD ‘VODKA’

Having first arrived in Russia in the 1870s, the early column stills enabled alcohol to be produced at a lower cost. Like the first grain whiskies being distilled in Scotland during the same period, distillers took advantage of this innovation to start creating vodka in its modern form. In addition to the traditional grains (rye and wheat) used by the countries that originally produced vodka, some had been using potatoes since the early 19th century, which were considerably cheaper. At the beginning of the 2000s, the introduction of Cîroc vodka by the Diageo group triggered hostility between the traditional vodka-producing countries and those that had been more recently converted. The composition of this vodka distilled in France, from grape alcohol, was a source of controversy... A controversy that was eventually brought before the European parliament! They were two points of view. Traditionalists believed that only spirits made from grain, potatoes or sugar beet molasses should be entitled to use the description of ‘vodka’. According to them, these raw materials were the source of a specific range of flavours that could enable each vodka to be distinguished. For the modernists, flavour, and by extension the nature of the raw materials, played an insignificant role in the production of vodka. It was the production method that was the key to vodka’s appeal. Beyond the debate on the importance of vodka’s flavour, there were economic and financial issues that also influenced the decision taken at the end of 2007. In 2006, a German politician suggested that the precise nature of the alcohol used should be indicated on the label in cases where it was not made from the traditional ingredients. This proposition was adopted, to the disappointment of the traditionalists, who had hoped for more restrictive regulations.

EASTERN OU WESTERN STYLE ?

The Eastern European and Scandinavian countries now not only take great care over the issue of the raw materials, whether its is grain, potato or molasses-based alcohol, but also over the distillation, responsible for their product’s aromatic identity, which they do not, under any circumstances, wish to see ‘softened’ by improper filtration. Canada and the United States relied on corn and molasses for their production. France was more unusual, in that it developed a process based on grape alcohol. However, the key characteristic of all these vodkas is their extremely subtle flavour, obtained through numerous distillations and filtrations carried out at the various stages of production, both at the start of the process within the still, and later on via a layer of carbon.

DEFINITION

Alcohol made from the distillation of a fermented mash, produced from grain (wheat, barley, rye, corn), sugar beet molasses, potatoes, or any other raw material of agricultural origin. Vodka, containing 96% alcohol, is then diluted to between 35 and 50% by the addition of spring water. Regarding agricultural raw materials, the European Union now requires that the nature of these raw materials be mentioned on the label, and that the vodka obtained contain at least 37.5% alcohol.

VODKA, STEP-BY-STEP

Step 1 – Raw materials & their processing

The grain (rye, wheat, barley, corn) are sprouted and the potatoes are cooked, so as to transform the starch that they contain into sugar. Once their starch has been transformed, these raw materials are crushed, or ground, and mixed with water to extract the fermentable sugars and produce a mash. Fermentation then takes place in a stainless steel vat, in order to avoid any contamination of the mash by bacteria that could affect the aromatic range. The yeasts used by distillers are usually selected for their high ethanol yield and their low impact on the production of flavours. When fermentation has finished, the alcohol is transferred to a still for distillation.

Step 2 – Distillation & filtration

Most vodkas are produced using continuous distillation in a column still. However, some distillers still prefer traditional pot stills, which produce very flavourful vodkas. In this case, the spirit may be filtered through activated carbon to remove its flavours. During the distillation phase, the master distiller decides when to make the cuts (between the heads, middle cuts and tails of the distillation) with a view to avoiding any contamination of the middle cut by the heads that are rich in methanol (presenting notes of solvents and varnish) or by the tails, that are equally toxic since they are saturated with fusel oils. This is repeated several times (usually 4 to 8); the successive distillations enabling the alcohol content to be raised to 95-96% and the extraction of a maximum of aromatic compounds.

Step 3 – Filtering & bottling

After distillation, the alcohol is filtered through activated carbon to remove any aromatic residue and render it as neutral as possible. Dilution is carried out with successive additions of distilled or demineralised water, until the desired alcohol content is obtained. A final filtering step is then carried out, before the alcohol is left to rest before bottling.

THE MAIN STYLES OF VODKA

Unflavoured vodka :

These account for most of the vodkas available on the European market. No classification has really been established, although it is possible to separate and categorise them by their raw materials.

For traditional vodkas :

Rye

This is the preferred grain for the production of Polish vodkas and some Russian vodkas. The influence of rye is reflected by notes of rye bread and a mildly spicy sensation on the palate.Wheat

The most popular grain and the first choice for Russian vodkas. Wheat-based vodkas stand out for their slightly aniseedy aromatic freshness and thick, luxurious palate.Corn

This grain is popular for its high alcohol yield and its aromas of butter and cooked corn.Barley

The least-used grain in vodka production, originally introduced by the Finnish, it is increasingly used in the production of English vodka.Potato

Having lost their popularity, potato vodkas are gradually making a comeback on the Polish market. They present a different, more creamy aromatic range to that of grain-based vodkas.For modern vodkas :

Sugar beet molasses

Used mostly in industrial vodka production.Other base alcohols

Some vodkas are also made from quinoa, and from grape alcohol.Flavoured vodkas :

These vodkas were originally produced by distillations carried out at home for recreational use, or in a medical setting for their healing properties. With a long tradition of flavoured vodka production, Russia and Poland have several hundred recipes (Krupnik, Jarzebiak, Wisniowka, Okhotnichaya etc.), the most well-known still being Zubrowska, made from bison grass. The most common aromatic flavourings for these vodkas are vanilla, ginger, chocolate, honey, cinnamon, and fruit flavours. These flavoured vodkas can be produced in three different ways : by maceration by adding natural essences by redistillation This tradition is not exclusive to Poland, Russia and the Ukraine. It is also alive and well in the Scandinavian countries, where flavoured vodkas are very popular in the summer.

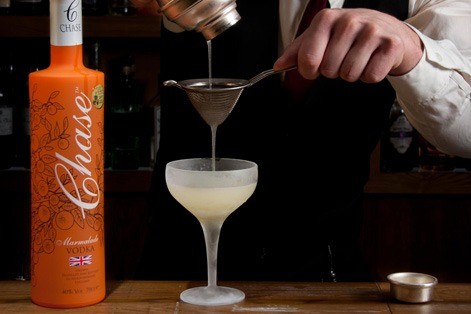

Whether it is consumed neat or in the form of a cocktail, vodka continues to attract a young, sophisticated clientele. In parallel to its success as a refined luxury product, it is also much appreciated for its more functional role as an excellent cocktail base, with a soft, smooth texture. Ultimately vodka only has one limiting factor: its relatively neutral aromatic range, which is especially true of western and American vodkas. Western consumers have yet to embrace the ‘Russian style’ shot of neat vodka enjoyed during a meal. However, the emergence in Poland and other countries of flavoured vodkas, produced by simple distillation, could be the key to attracting a new clientele.